Vidhi Agrawal

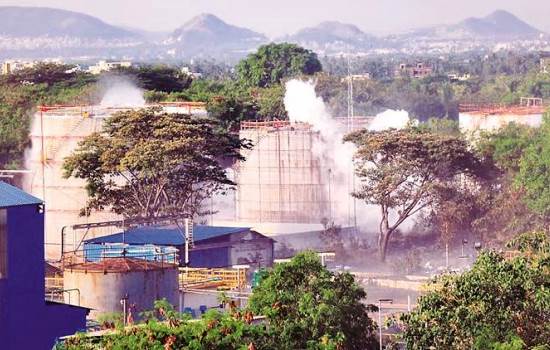

The dawn of 7th May proved to be a tragic start for the people who lived near the LG Polymers plant. At three, people woke up to a stifling smell doubting a gas leak, and started running out of their homes helter-skelter. Over 300 people were injured and admitted to the hospital and 12 people succumbed to the gas leak.

LG Polymers is part of the plastic resin & synthetic fibre manufacturing industry and is based in Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh. Polystyrene, high-impact polystyrene, expandable polystyrene, and engineering plastic compounds are made.

Upon investigation, it was found that there was a leak of styrene gas, which is flammable and have to be kept under at least 20 degree Celsius, regulating the temperature at frequent intervals.

Since the officials failed to monitor temperature, the high temperature instigated the gas leak. Also, it was highlighted that plant was functioning without environmental clearances since 1997.

The inquiry alleged that the leak occurred due to numerous technological deficiencies in the way the gas was stored: “poor design of the tank, [an] inadequate refrigeration and cooling system, the absence of circulation systems, and inappropriate estimation of specifications”.

This was identified by LG Polymers as “a serious lapse” and the accident was also the product of “poor management” and “a total breakdown of the emergency response procedures”.

The police in the Visakhapatnam district of Andhra Pradesh arrested 12 people, as well as the chief executive officer and LG Polymers Ltd directors (Poorna Chandra Mohan Rao Pitchuka, Chan Sik Chung, Hyun Seok Jang, Sunkey Jeong, Byungkeun Song, and one key management personnel, Ravinder Reddy Surukantiand)and sacked three officials for negligence.

The administration of the plant was charged by the Gopalapatnam police under IPC Sections “304 (culpable homicide not amounting to murder), 337 (causing hurt by act endangering life and personal safety of others) and 338 (causing grievous hurt), 278 (Making atmosphere noxious to health), 284 (Negligent conduct with respect to poisonous substance), 285 (Negligent conduct with respect to fire or combustible matter)” and also negligence.

The court named the AP High Court Bar Association president as amicus curiae in the case, taking up the matter on its own (suo motu).

Finally, it was held that , the LG Polymers India, the South Korean firm, has absolute liability for the loss of life and public health in the gas leak incident at its Visakhapatnam factory, while the NGT has claimed that the interim penalty of Rs 50 crore will be spent on victims’ compensation and environmental restoration.

The National Green Tribunal guided the preparation of a restoration plan by a committee consisting of two members, each from the Ministry of the Environment and the Central Pollution Control Board, and three spokespeople of the Andhra Pradesh government.

A bench of Justice Adarsh Kumar Goel, chairman of the NGT, said that a committee comprising members of the Ministry of the Environment, CPCB, and the National Environmental Engineering Research Institute will determine the final computation of compensation.

It also instructed the Chief Secretary of Andhra Pradesh to recognize and take effective action against persons responsible for the lack of law in allowing the company to operate within two months without legislative clearances and to send a report.

The NGT invited MoEF to set up an expert committee to recommend ways and means to overhaul the monitoring system to check and avoid infringements of environmental standards and to deter any possible recurrence of these in any of the toxic materials establishments.

The NGT claimed that the protection of people and the environment is of chief importance and that the safety of humanity and nature must be compatible with any economic or industrial activity, however possible.

Liability of LG Polymers

LG Polymers were held absolutely liable for their negligence. Negligence is a concept where the defendant owes a duty of care towards the plaintiff that was breached and resulted in damages where causation can be established.

Though it was evident that LG Polymers were negligent in management, they were held absolutely liable leaving them with no defence whatsoever.

Absolute liability popped up from the disastrous case of Oleum Gas leak ( M.C Mehta Vs. Union of India).

Absolute liability is a no-fault liability where a party is held liable even though it had no fault of his and wasn’t negligent. Under this the defendant must have brought a dangerous thing upon his land, it was put to unnatural use and the thing escaped causing damages.

Enterprises involved in a hazardous or intrinsically hazardous industry that present a possible danger to the health and welfare of individuals working in the factory and living in the surrounding areas owe the community an utter and non-delegable obligation to ensure that no harm occurs to anybody because of the hazardous or inherently hazardous operation it has undertaken.

The enterprise must be held to be under an obligation to ensure that the harmful or potentially dangerous operation in which it is engaged must be carried out with the highest safety standards and that the enterprise must be absolutely liable to pay for any damage if any damage occurs because of such activity and it should not be a response to the enterprise to say that it has taken all appropriate cares.

Further, in its affidavit of May 2019, part of an environmental clearance process, the South Korean parent company, LG Chem, claimed that, after obtaining an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), the company did not have a valid environmental clearance provided by the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC), corroborating the quantity generated and for operating activities.

LG Chemicals India, which is a member of the petrochemical industry, fits into category ‘A’ according to the EIA notification (amendment) of 2006 under the Environment Protection Act of 1986 and should be authorized by the MoEFCC any time they extend their plant or make a change to their manufacturing method after November 2006.

Without such approval, LG Chem extended its activities at the LG Polymers factory five times between 2006 and 2018. According to the affidavit of May 2019, it instead worked with state permits needed for starting a new business every five years with renewals since 1997.

Nonetheless, LG Chem spokesman Choi Sang-kyu told the Associated Press (AP) that the company had observed Indian laws and worked based on state and federal officials’ guidelines. He said that the affidavit was not an assertion of violating the law, but a promise of compliance with the law. Choi said that the company contacted the ministry after the 2006 notification and was informed that no approval was necessary.

Environment Secretary C. K. Mishra, however, told the AP that the plant would not have a clearance requirement in 2006, but that authorization was necessary for any expansion or output shift subsequently. Until 2017, LG Polymers had never sought federal permission, and according to the minutes of a briefing between the company and the Andhra Pradesh Pollution Control Board, the latter rejected the former’s application at its plant for the development of engineering plastics.

A representative of the state pollution board, however, said there was no data about any order by the state government to prevent the activity of the plant. In 2018, to increase its production capacity of polystyrene, a plastic used to produce bottles and lids, the company applied for environmental clearance for the first time.

The Ministry of the Environment submitted a request for review, citing that the company had no clearance for the chemicals it was already producing. The company withdrew the request when applying for a retroactive clearance given by the ministry as a one-time amnesty to businesses in 2018, which remained pending until the fatal leak happened.

Officials and legal experts such as Mahesh Chandra Mehta, an environmental lawyer, suggested, as per the AP, that the plant seemed to work in a legal grey area, with the environmental clearance needed under central guidelines whereas the compliance was to be taken care of by the state executives.

There is no evidence to date that the lack of environmental clearance played a role in the catastrophe. As the plant has run for years without any approval, experts are also suspicious. Mehta also asserted that many such industries operate without a clearance, which shows how fragile the environmental laws are in India, which has most of the most polluted cities in the world to its name.

Dr. B. Sengupta, an environmental scientist and former head of the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), said that only considering the pollution and not considering the protection of the site is allowed by the state. Federal clearance, on the other hand, assesses hazards related to the handling and storage of hazardous materials, the prevention of future disasters, and disaster reduction.

The leak enveloped five villages spreading to an area of 3 km. People faced problems with their vision sight and breathing. Many fell unconscious on the streets.

The National Human Rights Commission of India (NHRC) informed the Andhra Pradesh Government and the central government the same day as the tragedy that it found its occurrence a grave infringement of the fundamental right to life in India.

The NHRC was awaiting a comprehensive report in its notice from the Government of Andhra Pradesh on rescue missions, medical care, and rehabilitation. It also demanded that the Union Ministry of Corporate Affairs examine any potential violations of the law on health and safety in the workplace. Within four weeks, both reports were scheduled to be delivered.