By Venkatesh Agarwal-

Background

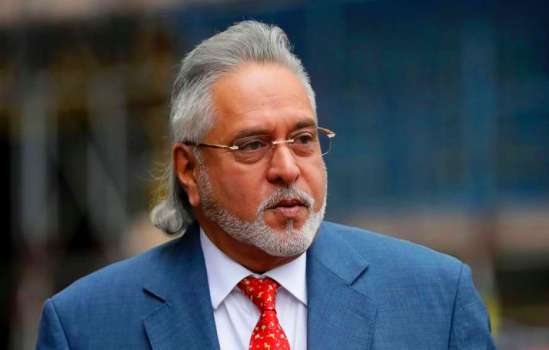

Mr. Vijay Mallya’s recent extradition order passed by the Westminster Magistrate Court in the United Kingdom on December 10, 2018 surely comes as a huge sigh of relief for the government and the Indian banks now under enormous pressure, with a long list of bad loans and absconding promoters. The UK order has now been taken up quickly by the special PMLA court in Mumbai that ruled on 5 January 2019, Mr. Vijay Mallya was a ‘fugitive economic offender’ under the Fugitive Economic Offenders Act, 2018 (“Act”).

Introduction

The aforementioned Act was first envisaged under the Union Budget for 2017 and was initially implemented as an Ordinance. With the assent of the President, this Act was adopted and was declared to have come into effect from April 21st, 2018.

The preamble to the said Act notes that the act seeks to provide for steps to prevent fleeing economic criminals from evading the Indian judicial process by staying beyond the control of Indian courts and protecting the sanctity of the Indian rule of law.

The Act depends extensively on Money Laundering Prevention Act 2002 (“PMLA”). Most meanings and requirements are the same as in PMLA and hence it would not be completely incorrect to even label the aforementioned Act as an additional act to PMLA. Please notice, however, that both Statutes are targeted at pursuing specific goals.

Main Features Of The Act

A specific structure is set out below for the aforementioned Act:

A “fugitive economic offender” means any person against whom a warrant of arrest has been issued in respect of a scheduled offense by any court in India, who-

(i) He has fled India to escape prosecution; or

(ii) Refuses to return to India to face criminal charges while abroad;

“Scheduled Offence” under the Act is simply a collection of current crimes (provided that the cumulative amount concerned is greater than Rs. 100 Crores) under different laws such as the Indian Penal Code , 1860, Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881, Prohibition of Benami Property Transactions Act, 1988, Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988, Companies Act, 2013, Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002 etc.

The said Act applies to any individual on or after April 21st day, 2018, who is or becomes a fugitive economic offender.

An application by a Director or Deputy Director (as specified in the PMLA) to designate a person as a ‘fugitive economic offender’ can be made under S.4. Under S.5 of that Act, the Manager or the Deputy Manager may continue with the attachment of assets, subject to receipt of approval from the Special Court; if the property is a victim of crime or some other property (Including any Benami property) owned by a wanted fugitive economic offender. The Special Court here applies to the Sessions Court appointed as a Special Court under section 43 of the PMLA, sub-section (1).

In relation to the aforementioned, S.5(2) further calls for the attachment of property by means of a non-obstant provision before the claim for registration of a convicted economic offender is made. The annexation of any property under this section shall continue for a period of 180 days from the date of the annexation order or such other period as the Special Court may extend. Nevertheless, in such a situation, the appeal under S.4 must be made within 30 (Thirty) days from the date of any provisional annexation.

Under S. 12, The Special Court may designate a person as a fugitive economic offender after being satisfied and for reasons to be reported in writing. I properties that are the result of a crime, whether owned or not by the offender; and (ii) any other property (including personal and benami property) owned by the offender; shall be confiscated from the offender;

S.14 is a special clause of the Act the forbids a convicted economic criminal from initiating / continuing / defending any civil charge. The clause goes a little farther and also disallows a limited liability corporation or a business from the same if a criminal industry has been proclaimed by its founder or main management workers or significant shareholder or someone with a controlling interest.

With regard to the presumption of evidence, it is the Manager (as specified under the PMLA) or the agent appointed by the Manager who will show that an entity is a fugitive economic offender. Nevertheless, if it is a case of another party alleging bona fide involvement, then the responsibility of demonstrating his innocent stake in the property and legitimacy of his assertion falls on the aforementioned individual.

The Act shall extend to all of India and shall have effect, in spite of anything inconsistent therewith contained in any other law and further, it shall be in addition to and not in derogation from any other law in force for the time being.

Analysis

The first thing that comes to mind is whether the said Act was absolutely essential or is it a case of a futile legislative action taken in haste to calm the agitated common man in the light of recent monetary scams of high value. Like PMLA, this Act refers directly to various other statutes and includes scheduled offenses in accordance with those statutes, but it covers a lot of fewer offences as compared to PMLA.

The reasoning behind this narrow approach may be due to the fact that, unlike PMLA, where confiscation and disposal of property only occurs after the conclusion of the proceedings, the said Act provides for the confiscation and subsequent disposal of property (whether located in India or abroad) on the merely declaration of an individual as a ‘fugitive economic offender’ where the individual is a ‘fugitive economic offender’ where the person does not return to Indian jurisdiction.

Such a punitive clause is likely to have a significant deterrence impact on the accused and would certainly compel him to confess or at least appear before the competent authority in India (either himself or through a designated attorney) and this is what seems to be the legislative aim here.

The seemingly arbitrary section 5(2) may be blamed for not being in line with the fundamental standard of law, i.e. ‘innocent unless proved guilty’. The clause is a significant legislation allowing the Enforcement Directorate, the law enforcement agency or any other relevant authority to scan, seize and add assets even without commencement of any proceedings.

In fact, as mentioned above, the authorities can only dispose of the property after a span of 90 days from the delinquent economic offender’s date of declaration.

This confiscation of a preliminary conviction is not a completely new concept. It was stipulated in the United Nations Convention against Corruption (“UNCC”), ratified by India in 2011.

Article 54(1)(c) of the UNCC allows the signatory countries to consider taking the necessary measures to permit the confiscation of such property without a criminal conviction in cases where the offender cannot be prosecuted for death or absence. That Act embraces the same concept.

In addition to the above, it’s also necessary to illustrate the domestic situation and the path our courts have taken. These specific requirements also occur in several other laws, such as the clause of land seizure under the Smugglers and Foreign Exchange Manipulators (Forfeiture of Property) Act, 1976 (which was constitutionally upheld by the Supreme Court in Attorney General for India vs. Amratlal Prajivandas[1]); provision of freezing of the company’s funds by the Serious Fraud Investigation Office under the Companies Act, 2013 and, inter alia, clauses of the Income Tax Act 1961.

S.5(2) of the Act , which allows for the attachment of property on merely suspicion until the arrest of a suspected fugitive economic offender and/or the commencement of any proceedings, that, on the grounds of its constitutionality, be questioned for being contrary to fundamental doctrines of justice. We believe that although the authorities may misuse or exploit this provision, it is a valid concern; the intent of the legislature of compelling absconders to surrender has to be kept in mind too.

In addition to that, in Sushil Kumar Sharma vs. Union of India[2] and Mafatlal Industries Ltd. and Ors. vs. Union of India[3] the Supreme Court held that the mere possibility of abuse of power does not constitute a ground for breaching the provision on the grounds that it is substantially unreasonable or ultra vires or unconstitutional. In any unjust situation, the court will also set aside the action / order / decision by maintaining the rule of law and offer the aggrieved party sufficient relief.

J.Sekar and Ors. vs Union of India and Ors.[4] would be the most important decision in here. In January 2018, the Delhi High Court affirmed the constitutionality of the second proviso of S.5(1) PMLA. The said non-obstante proviso is identical to the S.5(2) of the said Act. It enables the qualified authority under PMLA to immediately add an accused’s property on merely suspicion and without forwarding any report to the magistrate under Code of Civil Procedure, 1973.

But the appeal is pending in India’s Hon’ble Supreme Court at the moment. Given the identical existence of these clauses, the ultimate result of the case may have a substantial effect on the aforementioned Act.

S.14 disallowing civil proceedings is a sweeping section that also disallows a limited liability partnership or a company with which a fugitive economic offender may be involved from initiating or defending any civil proceedings. This is an unnecessarily wide and strict provision, particularly since the said Act does not in fact adjudicate a person’s innocence or guilt but merely declares the person to be a fugitive economic offender.

Chances are relatively good whether this provision’s constitutionality would be debated in the immediate future. In fact, in Anita Kushwaha vs Pushap Sudan[5], a Constitution Bench of the Hon’ble Supreme Court of India held ‘access to justice’ as a facet of the right to life guaranteed under Article 21 of the Constitution and also a part of the right to equality under Article 14 of the Constitution in Anita Kushwaha vs Pushap Sudan.

Although the said Act allows for a maximum of 90 days from the date of the declaration order until disposition of seized assets, it is curiously vague on the timeframe during which the Special Court will rule on an appeal under the said Statute. This may theoretically prolong the trial, especially in situations where the accused defendant appears through a solicitor.

While the right to defend itself should not be denied to an alleged offender, the absence of any fixed timeline gives the accused too much leeway to delay or stay proceedings without actually presenting himself to Indian authorities.

The prescribed threshold for offences of Rs. 100 Crores may allow many wrongdoers to evade the provisions of the said Act. In addition to the monetary interest, for the purposes of the Statute, the essence of the crime will also be recognized.

Although the above Act protects foreign properties and calls for a letter of complaint to be submitted to foreign states, the fact remains that India has a bad track record of extradition. More than 150 petitions for extradition remain pending with different foreign countries until April 05, 2018.[6] Thus, the deepening of international ties needs to be granted due importance, simplifying of extradition procedures and culmination of more robust extradition arrangements/treaties.

From a bare reading of the said Act, it appears that only a Director or an officer who is not below the rank of a Deputy Director may qualify under S.4 for an individual’s declaration as a fugitive. There is no scope for any other person to directly or even indirectly bring in an application. The reason for that omission is unclear.

PMLA S.62 calls for punishment by police in the case by vexatious searches by the policemen. Given the similar nature of the laws, a similar provision under the said Act would have been prudent.

The said Act places reliance on the preponderance of probabilities as the standard of proof that the Special Court will be using. Although this is a lower parameter compared to the general concept of demanding facts for conviction of crimes beyond reasonable doubt, the purpose of the stated Act should be provided due weighting aimed at getting the accused criminal into the Indian jurisdiction and not adjudicate upon and/or penalise the alleged offender.

Needless to say, it remains to be seen how the said Act would work in tandem with existing statutes, particularly with respect to property attachment and duties recovery under different statutes before different fora.

[1] Attorney General for India vs. Amratlal Prajivandas, AIR 1994 SC 2179.

[2] Sushil Kumar Sharma vs. Union of India, (2005) 6 SCC 281.

[3] Mafatlal Industries Ltd. and Ors. vs. Union of India, (1997) 5 SCC 536.

[4] J.Sekar and Ors. vs Union of India and Ors., (2018CriLJ1720).

[5] Anita Kushwaha vs Pushap Sudan, 2016 8 SCC 509.

[6] Question No. 4338 in Rajya Sabha answered on 5th April 2018.